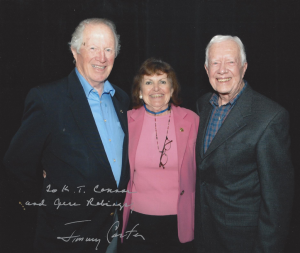

Dr. K.T. Connor was a Senior Adjunct Professor with the MPPA program until recently, for over a decade and brings a wealth of experience in ethics, business as well as public leadership. She served as the Managing Director of Applied Axiometrics. She is the head of a virtual collaboration of consultants using decision-theory-based assessments in selection, development, coaching, team building, and succession planning. In this short interview, she shares some insights into public leadership, ethics and her work and association with former (late) President Jimmy Carter.

- Tell us about your association with Jimmy Carter and the Carter Center

When I lived in Georgia, I was often driving from my island off the coast, to the Carter Center in Atlantic, for both conferences and then meetings. And I was so delighted to learn more and more about what the Carter Center was doing, and why. That’s when I became so impressed with the humanity and value-based approach of Jimmy Carter.

I continued to learn more about Carter when I would often attend his gatherings in Lake Tahoe, San Diego, and of course, Atlanta at the Center. It was so easy to relax at his events, and he was open to all of us.

I was so glad to get to see how down to earth Carter was. When I went to various places with him and others, he was so open to all there. And he still invited us down to his hometown, and it was so clear he was so much a part of the community.

One trip I flew from Atlanta to the west coast with all attending the special event at Lake Tahoe. He was so good going all over the plane and talking to all of us. He was relaxed and open and walked up and down the aisle to have a chat with all of us.

- Carter is often spoken about as an ethical leader, do you agree? Can you elaborate on why you agree or disagree?

I certainly agree that he was an ethical leader. I followed his role as President of the United States, and saw that he valued service above self-interest. Yes, that often resulted in looking less effective now and then, but from what I saw, it was consistent with his desire to serve. He was open even to those who ran against him, as Gerald Ford’s son notes at Jimmy’s funeral. (He shared that Gerald and Jimmy became good friends, even though Carter had gotten more votes on the election than Ford.) Even when President, he showed he had principled leadership, and valued decency and justice as well as caring for others. Because of the complexity of US Presidency, his caring became even more obvious when he developed the Carter Center.

When he was no longer President, he decided to maintain his desire to serve, and value all, and created an impressive goal for the Carter Center. He developed an organization to work to help even powerless people, to have them have skills, knowledge, and resources to improve their own lives. This improvement included disease prevention, democracy increase, and human rights safeguard.

He also was known to commit to truth, not lying, and to the importance of improving oneself, as well as helping others do so.

- What aspects of public life today are different from say, the 1960 or 70s when Carter was active, politically?

When he was active politically, he was still learning how to serve others. He also absorbed values through his church to care for others and oneself, and to promote peace. He did now and then make a decision that did not turn out as he expected, and he was seen as not one to reelect. As our country grew, much energy went to divisiveness and race division. But gradually we as a country tried to bring all together. Carter’s decision did contribute some of that.

Carter’s involvement with his work at the Center, on the other hand, showed what he had learned, in order to be more effective with his goals. His dealing with helping people in various countries, including our own, created wide efforts to help others.

- Does public service motivation impact ethical values?

I feel it does if it focuses not only on oneself, and one’s ability to lead and serve, but also on others, especially those in need.

One of the things we learn from good servants is something we can learn from Jimmy. Power is often maintained to be desired by many. But Carter slowly showed this was not why he served.

He seemed to know that some power was appropriate. But also it seems he also felt that respect for others, and even care for others, was essential. In no time that I saw him, did he show he was worth bowing to. Rather, he could be seen as so humble, so many times.

This should be a model for all in public service. It is a real service. Yes, they should make sure no one violates the ability to provide the service required. But they should also care not only for themselves, but definitely, also for others.

- What are specific ways in which Carter’s life can serve as an example for young public servants today?

One major thing I feel is to be sensitive to bringing people together, not apart. This can be a challenge now and then, but they should also be sure to build the skills needed to meet the goals of their position. But public service is service to others, to those who depend on the service. Public ethics lets the public servant value being socially constructive, idealistic, altruistic, and creative. This will enrich our world and hopefully bring us all closer together.

- Any other thoughts on ethics and public service?

I feel someone in public service deserves to be comfortable with themselves, and value themselves. I also feel, however, that real public service is not to just focus on power. It is not being seen as needing to have others feel less about themselves, so that the servant can be seen as more perfect. Real service is reaching out to all, especially those for whom they are assigned, to help them grow and perform. And it is good that they did this also for others. Jimmy Carter definitely showed that this was good to do.